Editors Note: This guest post is part of the Blog Carnival of Blogging While Brown for Black History Month 2014. -M.P.

By now, you’ve likely heard of Amiri Baraka’s death and at least something about his life and work, even if you’re not into poetry or African American history. Baraka was indeed one of the giants of the African American literary and historical landscape and his career neatly tracks the trajectory of social movements as well.

He’s given credit as being one of the founders and key people in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s-70s. Artists who embraced the movement saw themselves as the cultural wing of the Black Power Movement and sought to create socially conscious, politically engaged art, but Baraka was far from the only one. It’s impossible to do even a brief overview of all the collaborators here, but I can highlight a few other individuals and groups from the Black Arts era who aimed their art straight at the common people and created politically engaged art that would not only attempt to reach people who weren’t into poetry, but also raise their political and race consciousness.

As a result, it was common for poets to release their work on records, sometimes with musical backing. Here are a few examples. Some are still available on CD (or records, through eBay); many will come up from a YouTube search.

The Last Poets released their self-titled first album in 1970 on Douglas Records. It would be the first of several released by a shifting collective who both produced some enduring work that’s associated with the Black Arts and also represent the type of stresses and problems nearly any artistic collective runs into. Their 2012 This is Madness compilation collects some of their classic work on a 2 CD set. Two members – Abiodun Oyewole and Umar bin Hassan – still perform under the Last Poets name.

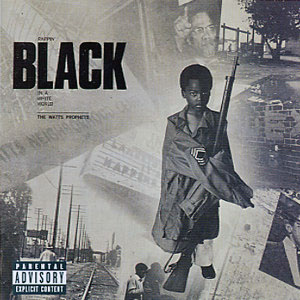

The Watts Prophets may have never achieved quite the level of notoriety that The Last Poets did, but are a good example of the work emerging from the Los Angeles cultural landscape. Their work features collaborative poetry with nods to jazz and the Blues and has similar incisive social commentary to many Black poets of the era. Their 2 key releases, Black Voices on the Street in Watts and Rappin’ Black in a White World are available on a compilation CD — Things Gonna Get Greater: The Watts Prophets 1969-71 — but it appears to be out of print.

Jayne Cortez also hailed from Los Angeles. Cortez’s work draws on jazz and the Blues and her fusion of social commentary into her work makes it seem nearly effortless. She began releasing records in 1975 on her own Bola Press label; much of it backed by her Firespitters band (which includes Denardo Coleman; her and Ornette’s son). Her recorded work is hard to find now and most from the 1970s-80s haven’t been released on CD.

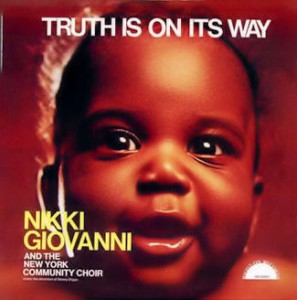

Long before poet and distinguished professor Nikki Giovanni’s words comforted a Virginia Tech campus mourning from a shooting, she made a name for herself in the Black Arts Movement with several albums of spoken word poetry and most are available on CD. Her book of collected poems gives a full view of her career, but you have to hear Giovanni to really appreciate her. One starting point is The Truth is on its Way, recorded with the New York Community Choir. The track “Ego Tripping” gives a nod to the African consciousness that bloomed during the period and her rapping over handclaps and call-and-response sounds like as much of a precursor to hip hop as you’ll find.

Next to Baraka and The Last Poets, Gil Scott-Heron may be the best known from the era, especially his popular work “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”. His discography goes far beyond that, however. The Evolution and Flashback compilation collects much of his early work.

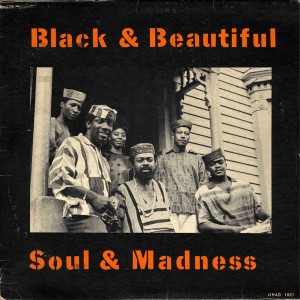

I’d definitely be remiss if I didn’t mention Baraka’s work. Black and Beautiful Soul and Madness, done with the Spirit House Movers, is available on CD. People wanting more recent work should try to find The Shani Project, a tribute to Amiri and wife Amina’s slain daughter which features their Blue Ark band, which the two performed with for nearly 3 decades, and he’s recorded with quite a few collaborators ranging from the New York Art Quartet to the Roots.

Obviously, there are many more who could (and probably should) be on the list: (Wanda Coleman and Sonia Sanchez get honorable mentions, though Sanchez has few commercially released recorded works.) People looking to dig deeper should also check out Pat Thomas’s recently released book Listen Whitey!: the Sights and Sounds of Black Power 1965-1975, which collects an impressive array of recorded spoken word, speeches, and jazz from the era. The companion CD is a good starting point as well and much of what I’ve mentioned here can be found on YouTube.

In a time when pop music often seems to be in full speed crazy mode, it’s helpful to look back in the not-so-distant past to artists who worked together and dared to put out bold, uncompromising work. There are new artists who are taking up the call to produce art that means something and challenges. While it may be a while before we see another generation as prolific and focused as the one that saw themselves as the artistic wing of the Black Power movement, making sure we pass the tradition on is one important way of honoring their work.

Bio: Hank Williams is a PhD candidate in English and Africana Studies at the CUNY Graduate Center and teaches at Hunter and Lehman Colleges and The City College of New York. He can be found on Twitter @streetgriot