Socialism is among the current topics of discussion in the 2016 election cycle. Due to the groundswell of support emerging for Bernie Sanders and his brand of Democratic Socialism, many are engaging in conversations around what the term means. In a country where Marxism is derided as Un-American, undesirable, and utopian, this represents a slight step forward in the political discussions had in the public square. Now, as to whether or not this interest in socialism is only due to the fact that it is part of the discussion of the election cycle, or if it’s deeper rooted remains to be seen.

However, this provides an opportunity for those who are so inclined to talk about socialism and radicalism to talk about the ins and outs of what this means. Since it is Black History Month, I believe now is a great opportunity to talk about the tradition of Black figures who have advocated socialism in this country. Also, interestingly enough, there are figures from our collective past who have expressed a view of socialism that leaves room for belief in God. One such figure is Reverend George Washington Woodbey,a Christian Socialist preacher operating out of San Diego in the first decade of the 20th century. Born into slavery in Tennessee, Woodbey was a self taught reformer who embraced the Populist movement of the 1890’s and later embraced socialism in the 1900s.

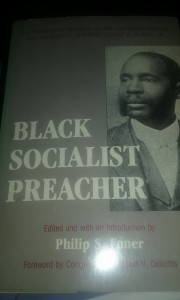

Historian Phillip S. Foner authored a book about George W. Woodbey, and collected the pamphlets of his teachings in that work. The work, titled Black Socialist Preacher, is a compilation of essays on matters revolving around religion and socialism from Woodbey’s perspective. In ideas that could easily have been the forerunner to liberation theology, Rev. Woodbey makes connections between being a Christian and practicing the economic messages of the Bible on earth through socialism.

In addition to outlining what socialism is and how to achieve it, Woodbey polemicized against his contemporaries. There are essays where he takes on the ideals of Booker T. Washington, criticizes both the Democratic and Republican parties, and takes to tasks the unbending nature of the Socialist party of the early 1900s of its views on the necessity of being an atheist before one can be one over to socialist views. While historically, the two are linked, they can be decoupled for the purpose of winning people over to the struggle for better, which should be the ultimate goal. At a time where many of the “old questions” are being asked anew, and some are looking to answers from a presidential candidate that espouses the idea of Democratic Socialism, Black Socialist Preacher is a resource to take a look at for ones self. Aside from the obviously antiquated late 19th century and early 20th century references, it’s a good point of reference for those who are genuinely interested in the Black radical tradition in America.

One comment